Meet Vance | Vance's CALL resources page | Presentations & Publications

![]() Save this page to your DEL.ICIO.US

account and TAG it there

Save this page to your DEL.ICIO.US

account and TAG it there

Meet Vance |

Vance's CALL

resources page | Presentations &

Publications

Multiliterate approaches to writing and collaboration through social networking

This is Lecture 1 in my part of a short course on writing on the Internet "Learning to write in a global and plurilingual world" given during the XXVI Summer Courses of the University of the Basque Country in San Sebastian, Spain, 11th-13th July 2007: http://www.sc.ehu.es/cursosverano; Date and time of delivery: July 11, 2007, 10:15 GMT (12:15 in San Sebastian, and for the time where you are: http://tinyurl.com/yvjkq9)

by Vance Stevens Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Navigate to: Writing Portal | Lecture 1 | Lecture 2 | Lecture 3

Lecture 1 is an explication of Web 2.0, multiliteracy, and its impact on the nature of learning in general, and on writing in particular. The first talk will draw from my online multiliteracies course: http://www.homestead.com/prosites-vstevens/files/efi/papers/tesol/ppot/portal2007.htm.

Lecture 2 discusses the general playing field for writing and collaborating online, as the two are closely inter-linked. There is no real writing without a need to communicate a point, and therefore an audience is required. The nature of that audience is discussed, both from the point of view of collaborating 'writers' and commenters on their blogs.

Lecture 3 is more technical. Taking the concepts laid out in the first two talks, how do we do it? I will discuss Writingmatrix and what I have learned about tagging and aggregation since mounting that project, and carry this through work done by Barbara Dieu, Rudolf Amman, and Aaron Campbell on http://www.dekita.org (Dieu and Stevens, 2007), and finally show some of what Robin Good has shown me about newsmastering using http://www.mysyndicaat.com.

Fitness

buffs exercise overlooking the town along the beach

150 word abstract: Several analogical literacy practices have migrated to Internet. Now common genres of writing are emails, wikis, blogs, chats or web pages, and more. We not only read on a screen and write with the keyboard and mouse, but we are expected, now and in the future, to understand, find, analyse, critique, organize, and assimilate information from numerous other media besides. Furthermore, we are expected to create and communicate appropriately in numerous and often only just emerging media genres. How has Internet changed literacy practices? Which are the most relevant electronic genres in L2 learning, why, and how can we use them? To address these questions I draw from an online course I teach annually for the TESOL Certificate Program: Principles and Practices of Online Teaching, where I address the many issues involved and provide a plethora of links in many media modalities to provoke your thinking on the subject.

This course is being revised with the summer sessions in San Sebastian as primary audience temporarily, to be shifted to TESOL participants in September: http://www.homestead.com/prosites-vstevens/files/efi/papers/tesol/ppot/portal2007.htm

The read-write society in the 21st century

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gmP4nk0EOE&eurl=

|

We are

currently preparing students for jobs that don't yet exist. Further notes from James Neill on the TALO list, Sept 28, 2007: here's a jazzed up version of "shift happens" http://shifthappens.wikispaces.com/Various+Versions+of+the+Presentation (which I discussed initially in Lecture 1 reflections http://7125-6666.blogspot.com/2007/07/social-change-challenge.html ) - it's basically facts & figures that suggest singularity http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_singularity is well under way - and that we should be moving with this future rather than stuck in the past, etc; a handy reference for those of us working in institutions which don't get it yet: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMcfrLYDm2U (6 mins) |

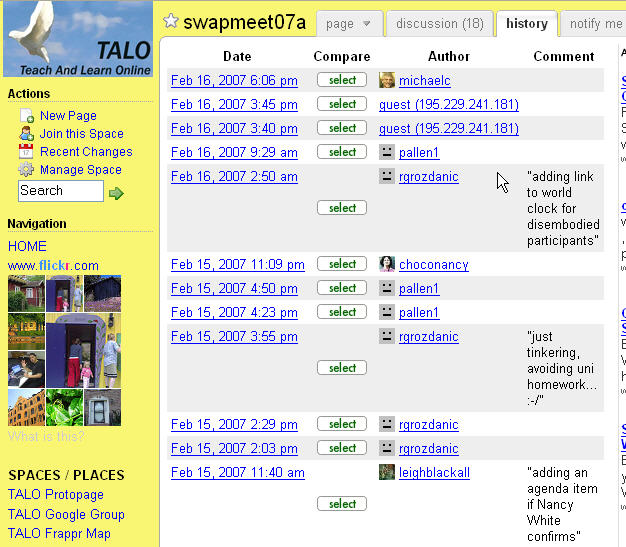

I recently attended an unconference, online (TALO Swapmeet 2007, http://talo.wikispaces.com/swapmeet07a). Now there is a concept that could take some explaining (alternatively, just look it up in Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unconference). In the first place it would not have been possible to have an online unconference at all ten years ago. Ten years ago, we were in the read-only century. You have to be a digital immigrant to have been aware of that. Digital immigrants and digital natives are how Marc Prensky (2001) divides the world of computer users. Digital natives grew up with computers and technology. Digital immigrants were raised in the good old days of snail mail and long distance phone calls and do not generally find technology to be second nature. If you are a digital immigrant, then probably you remember how things were in the read-only century.

The read only century is what Lawrence Lessig calls the time when web pages were static, one way conveyors of information, and top down disseminators of knowledge ("The 20th century was the only read-only century in human history, totalitarian, centralizing, controlling. The 21st is the return to read-write." Lessig (2006)). The "read-write society" is what he says we are returning to in this century thanks to the increasingly conversational nature of interaction available through the Internet today (see my notes under Lessig in the references).

In most good web sites today, there are numerous ways you can interact. You can leave a comment, take a poll, rate the site, review it, you can even subscribe to a service that tells you who else is on the site at the same time you are and contact them. You are not limited to doing this on other people's sites - you can make your own. You can easily set up your own web presence on other people's servers, for free, and they're falling over themselves to attract your participation. Once there you can upload or create text and augment it with digital graphics, audio, or video which you might upload or create on the site. Back in the read only century, you used to have to know some HTML, you had to arrange your own web hosting, usually had to pay for it, and bandwidth and the amount of space you had seriously restricted where you could park your large files. Nowadays, I upload sound files to Wikispaces just to give them a url so I can use them at other websites. Video would be more of a problem except that there are many fine services like blip.tv, Google Video, and YouTube who will not only give your videos a home on the web but give you the script to embed their players in your blogs and web pages.

So, what was I talking about? Unconferences, and how organizing one would not have been possible in the read-only century. An unconference is a gathering of professionals who agree in advance to let it happen as it will. Unfortunately the universe tends too heavily to chaos if left to itself, so some order has to be imposed. A good way to do that is set aside a few dates for the unconference and then put up a wiki and let anyone who is willing to present at the unconference write down what they intend to do. It's interesting how the wiki starts filling up with volunteers, and the event begins to take on vestiges of structure (whose History is recorded ... at the page above, clicking on any date will give you that rendition of the wiki, and the wiki can be reverted to any date as well). At the same time, you can set up a Frappr map (or Attendr, or a Cluster Map) and watch your unconference start to populate itself with faces and shoutouts. Eventually there's enough momentum that it starts to take on a life of its own.

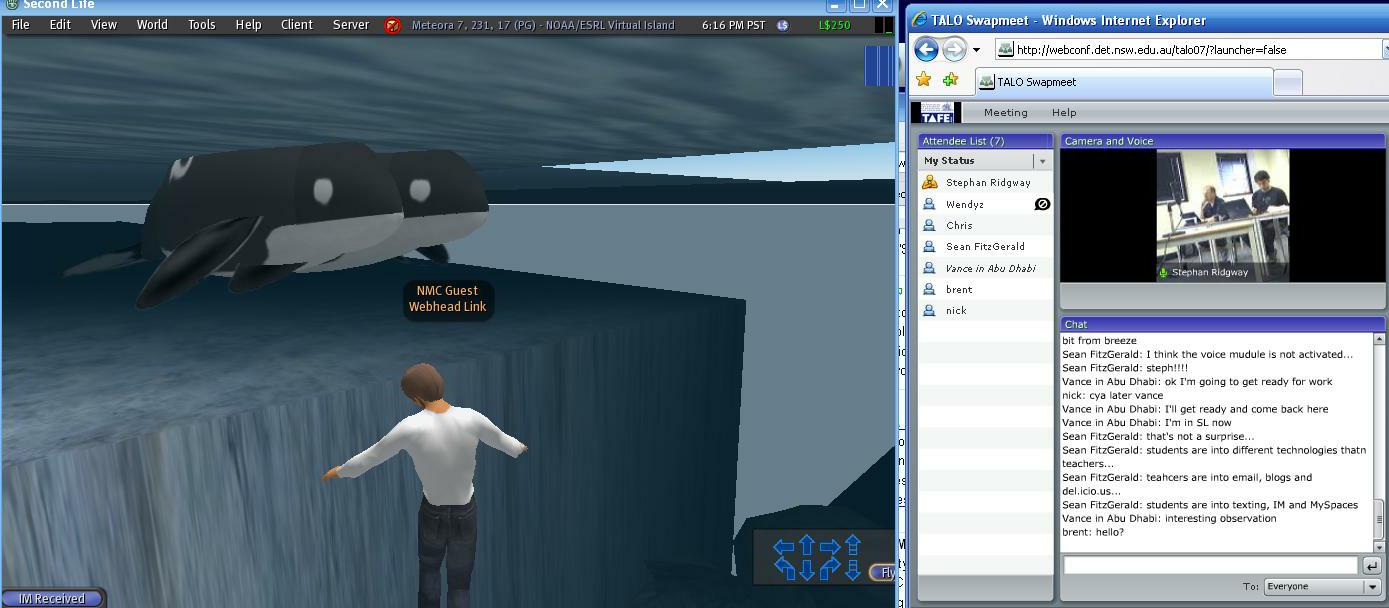

So the reason I'm thinking about this unconference I was attending, online, is that at one point, I was hanging out in Second Life, suspended in midwater actually, observing a pod of orcas, when in the Breeze chat, which I was also monitoring, I noticed that Sean FitzGerald had observed that "students are into different technologies than teachers ... teachers are into email, blogs, and del.icio.us ... students are into texting, IM and MySpaces." (These remarks appear in the text chat in the Breeze window below.)

Now this really got me thinking. Here's me, digital immigrant, refugee from the read-only century, and yes, I'm a teacher and the things Sean listed are what I think of as cutting edge technology: email, blogs, and del.icio.us. And in two out of three of those, I'm ahead of my colleagues, many of whom don't even know what del.icio.us is. The students meantime are texting with their thumbs, so much for what we think of as keyboarding skills. They are texting over mobile telephones, or Twittering even (Twitter twits can come in on your mobile phone). Texting, instant messaging and MySpaces are ways of communicating that appeal to digital natives, who work at what has been called twitch speed (Prensky, 1998; Katz, 2000), and for whom technology is "always on".

These are the people to whom many of us are teaching writing, and I have started out talking about unconferences, digital natives and immigrants, blogs, Twitter, Second Life, Breeze, etc. because they illustrate where many of us are coming from in the means we use of communicating with one another. Writing in the way that I have been doing so in this article, is a skill that will always be required, but its importance as a component in our means of communication has diminished. For a long time writing was the sole means of communication apart from speaking, and certainly it was for a long time the only way to preserve what we wished to record (aside from art and music). It remains true that an ability to write well is important and even crucial to the art of conveying ideas today, but the role of text in what we convey in digital format is no longer the only skill we have to master in order to communicate effectively throughout an online distributed knowledge network. (Lorenzo, Oblinger, and Dziuban, 2004)

Nowadays, after several centuries where print literacy was what was understood by the term 'literacy', educators are starting to think in terms of 'multiliteracies' (Unsworth, 2001). Multiliteracies was a term coined by the New London Group in 1996. Multiliteracies means literacy skills that help people communicate meaningfully in the media available to all parties in the conversations taking place with regard to that communication. Multiliteracies has many dimensions to it; Selber (2004) for example breaks the concept into its functional, rhetorical, and critical aspects, which basically means that to be multiliterate you must use technology fluidly, to the point where you use it comfortably, seamlessly, and control it rather than it controls you, you know how to communicate with others about how you use, develop, and repair technology, and you are able to understand and articulate the many impacts of technology on our lives and those of others in other walks of life and economic strata.

There are many interesting examples of how communication takes place among people whose muliliteracy skills are well developed; e.g. the interesting videos by Lee and Sachi LeFever); on RSS, for example:http://www.commoncraft.com/rss_plain_english. These utilize video and sound, and to the degree that these convey the message, little in the way of text (except that they might have been written out to begin with. As another example there is a video (Stevens, 2006) where I wrote a talk for a conference in Antwerp and then delivered it by placing a cam corder facing me at head level, and with my laptop right below that and my hand on the mouse, read what I had written while looking straight into the camera, then uploaded the result on Google Video and Blip.tv. In this case my writing was transformed into its analog representation and then digitalized at http://snipurl.com/vance2006antwerp).

Blogs lend themselves particularly well to the embedding of YouTube videos, Bubbleshare slide shows, flash animations and movies, graphics of all types, and embedded sounds. When these media files are hosted at Web 2.0 sites and spaces, typically the code for embedding them in one's own blog is available on the site, and equally typically, people seem to know how to use that code, or can figure it out, and make the media play on their own blogs and web pages.

One genre of multileracy where writing is key is blogs, wikis, and podcasts (especially where these are written out in advance). Terry Freedman's (2004-2007) project Coming of Age is an excellent example of what appears at times to be a book, or an ebook, and in its podcast form is a set of texts which can be clicked on and heard being read, or by subscribing to an RSS feed - but here again, what you are hearing is articulated writing, as the texts were prepared in advance and posted on the site.

An emerging genre, or buzzword if you like, for teaching using a multiliteracies approach is digital storytelling. Digital storytelling appears (to me) to incorporate constructivist principles in encouraging students to use whatever medium seems appropriate to convey what it is they want to convey. A good characterization of what digital storytelling is can be found in a podcast on the topic by Wesley Fryer (2006). The fact that the literacy cited here is oral literacy, and the means to record and convey it digital, is further illustration of the ligitimacy of this departure from the what would previously have been regarded a constraint on citing only printed matter in academic writing.

What is Web 2.0?

It's interesting to have Tim Berners-Lee's perspective on Web 2.0, when he was asked by Scott Laningham, host of developerWorks podcasts: "You know, with Web 2.0, a common explanation out there is Web 1.0 was about connecting computers and making information available; and Web 2 is about connecting people and facilitating new kinds of collaboration. Is that how you see Web 2.0?" Berners-Lee replied: "Totally not. Web 1.0 was all about connecting people. It was an interactive space, and I think Web 2.0 is, of course, a piece of jargon, nobody even knows what it means. If Web 2.0 for you is blogs and wikis, then that is people to people. But that was what the Web was supposed to be all along." Laningham (2006).

Despite the clear intent of its inventor, it is only now that his vision is being universally implemented, which might account for the wide acceptance of Tim O'Rielly's (2005) creation of the term Web 2.0 to label the trend on the Internet for tools to be created and shared for free at web sites which allow users to create web artifacts or upload their own files to in turn produce web artifacts which might be even hosted on the site, seemingly forever. There are hundreds of such sites and tools, and among them are many that lend themselves to writing, and in particular to the process of writing. I will be discussing both these aspects, technology at the service of writing itself in the form of sites for blogs, wikis, and Google docs, to take some examples, and for the process of developing ideas, particularly through collaboration online. (Sessums 2007)

I have cited a number of sites aimed at defining Web 2.0 by example, here: http://www.vancestevens.com/casting.htm#web20(mirrored at http://www.prof2000.pt/users/vstevens/casting.htm#web20. Some of these are noted below

.

The Blogosphere and the Long Tail

The Long Tail

blog: http://longtail.typepad.com/the_long_tail/

I'm not sure of the composition of my audience but I'm going to assume well over half are aware of blogs, almost half read them, and perhaps a quarter will be bloggers themselves. Many might already be collaborating in writing projects using wikis. (I have put a survey on the Moodle asking for this information - http://www.surveymonkey.com/s.aspx?sm=CoyrqVBRpKp5JvR82Chr2A_3d_3d).

When I talk about writing on the Internet, what do I mean? There's an old joke, which part of 'writing on the Internet' don't you understand? But in fact, we need to tease that out a bit, because there is 'writing' and we need to know a bit about what that means these days, and there is then again the Internet part of it, which encourages use of all sorts of back channels to writing, to the point where we return full circle to the question of, ok, what is writing these days?

This is how writing works in the blogosphere. It is uncontrolled by the forces to whom we have traditionally ceded control over what we read and write in traditional print media, and therefore in the classroom. Since the invention of the printing press, this control has been largely top down. That is, there are publishers who are presumed to be experts in their field who have become arbiters of that process, and though they might be influenced by profit or by politics, when we walk into a bookstore and pay for our reading matter we are buying into the notion that we are purchasing quality. The i's have been dotted, all the t's have been crossed, and the prose has been pasteurized through a series of editors so that the high level of quality of what we are about to read is maintained. And the ideas themselves have gone through a process that is designed to sell books, to ensure that quality, and to spare us from having to read something far afield from what we bargained for. If I'm going to buy this book to take home and read it before bedtime, I want to be reasonably sure that I'm getting what I paid for, that my money doesn't support causes much more radical than I am (or heaven forbid, radical on the opposite wing!), and that I will augment the part of my knowledge base that I anticipated needs augmenting, which might be one reason I bought that book.

The trouble is, there are other people in the bookstore, and the books there must compete for their custom too, and it turns out that this has a narrowing effect on what gets published depending on what publishers are willing to risk in their business. There are many in what is known as the long tail (Anderson, 2004) who deal in niche areas where there is need for expertise but little profit because that niche is too specialized to attract many with money (or other forms of power). The traditional publishing world was not catering effectively to many of these people, and it turns out that, whereas we all have in common a mutual interest in many centrist issues, most of us also inhabit many of these niche areas where previously our voices and those of our closest colleagues in these niches were not being heard, if indeed we were able to find one another at all.

The Question of Quality in Web 2.0

This is where you come in, You as in Time's person of the year (Grossman, 2006). Now, in the read-write 21st century (Lessig, 2006 - and: Tim Berners Lee (Weaving the Web, 1999) http://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/Weaving/) if you have something to say you can publish it online, and quite likely it will be found and attended too. You can create a blog. You can start a wiki. You can post photos on Flickr, you can create freely accessible and creative online presentations with those photos or with your PowerPoint slides. You can support your points with charts made in Gliffy or other concept mapping tools, or with real maps from Google earth. You can collaborate on spreadsheets to manipulate data necessary to your work, you can talk with collaborators in real time, not just text chat, and you can record your conversations using free tools (like audacity, and virtual audio cables which you need to get both sides of a Skype conversation) or manipulate recordings that others have made and shared via creative commons, non-commercial, share and share alike, license (another significant break from traditional publishing). Basically you can collaborate. And you can publish what you produce, free, online, in text, video, or audio, or in any other kind of digital medium, and share it, and use what other people have produced on the same basis.

And what do you lose? Quality? That's what a lot of people seem most concerned about before they have gained much experience with the system. When you buy that book you can be reasonably assured that there is quality inside. It's been through a quality control process. True. It's also been through a filtering process, a process perhaps bordering on censorship, or that will introduce some other form of bias. But granted, it will be hard to avoid bias in anything you read (though it's somewhat galling to have to pay for bias), so perhaps people are concerned more about quality here. But let's talk about both, in balance.

One classic debate on this issue is whether tis better to consult a published Encyclopedia or Wikipedia, and let's leave cost out of it. Wikipedia for obvious reasons carries more current articles - the new Pope was named in Wikipedia the moment the smoke left the chimney (according to Stephen Downes, who himself had tried to be first), and you'll never find many of the terms or programs I've mentioned in these lectures in a printed encyclopedia, but you can look up almost anything I have mentioned here in Wikipedia. So currency is better with Wikipedia, and also scope (there are something like 750,000 articles in Wikipedia). Also the words in those articles are machine-searchable in Wikipedia, not so in any printed work, where we must rely on a relatively crude index. So on four counts (cost, currency, retrieval, and scope) Wikipedia seems preferable, and the what remains is the integrity and bias of that information; in other words, are there serious compromises to integrity and bias that would compromise the validity of what you find in Wikipedia? You now have to pay $30 to read the article in Nature Magazine comparing accuracy in Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Brittanica, which found them not far apart on that score, although considering that some colleges have banned their students from citing Wikipedia articles in reports, there would appear to be some concern (or are they just trying to force the students to use something besides Wikipedia as a definitive reference on every question? ).

I guess it depends on which nano-second you looked. There is a complaint that with wikibooks used in classrooms, teachers would have to have a locked down copy of what they saw one day and intended to show to students the next (or risk big surprises in class). There is no way to lock-down Wikipedia. Articles can change one moment to the next. But in general changes tend to be well mediated. In practice the wisdom of crowds prevails (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wisdom_of_Crowds -- it's only on the streets that mob riots break out; and even in aberrant cases of cyber-bullying and flame wars, a community tends toward the middle). What we see with Wikipedia is that strong biases tend to be expunged, and people are as a result careful with what they write in order to avoid attracting modification. Even cases of vandalism or spam tend to be dealt with quickly, either by humans or bots that continually troll Wikipedia.

For an excellent example of how wikis undergo change over time, and how a distributed network operates to mediate both vandalism and radicalism, check out the fascinating screencast of the evolution of the article in Wikipedia on 'Heavy metal umlaut": http://weblog.infoworld.com/udell/gems/umlaut.html .

Reading and Writing on the Read-Write Web

You're probably wondering if I'm talking about reading or writing here, but you might agree with me, that reading are writing are two sides of the same coin, utilizing in many cases similar cognitive and mental processes. Bill Grabe writes nicely about reading being a conversation with a text. There is much written on the processes of reading and writing resembling conversations with text, with thought, with wording, playing with words, and -- bringing it back to writing -- with anticipating an audience reaction, a real or imaginary one.

When we talk about people making changes in Wikipedia we are talking about a constant play with words, meaning, context, and facts -- a constant interaction between readers and writers, and in the case of Wikipedia, but crucially NOT with a printed encyclopedia, where the roles of readers and writers are completely distinct, anyone can take the role of reader or writer at any time. This is a huge breakthrough for consumers and creators of text. It is a role afforded particularly in wikis, and is a near-perfect match for the conversational nature of the read-write web; where the conversations envisaged in the Cluetrain Manifesto play themselves out in schools and in other places on and offline where people interact. (Locke et al, 2001).

The distinction between readers and writers is less well maintained in blogs. In blogs there is generally an author whose point of view predominates, though others have a chance to 'comment' - normally in a lesser capacity. Conversations can be sustained in this way, though comments in blogs may, with some exceptions, not be taken seriously enough to be cited or linked to directly in others' postings. For a comment on a blog posting to take the same stature as the original posting, that comment would have to be made as a posting in its own right in the commenters's blog. The second party in the conversation would then link to the original posting.

But this would be a one-way link. Readers of the second posting would see the link and click to the posting that started the conversation. But, how would readers of the first posting be aware of the second? Or if there was a third comment made in yet another blog post somewhere relating to the first two, how would the original posters be made aware that the conversation was continuing in some other corner of the blogiverse? Or set in a more specific context, how would the students and teacher in one class of writers know when students in another class, or readers anywhere in the world for that matter, had found something worth noting in their blog postings and blogged about it themselves? (Barbara Dieu says she uses "cocomment, which tracks all the conversations." - I'll look into that, Vance)

This is where Web 2.0 gets interesting. There are many ways to find and filter content in the blogosphere. We'll go over these in some detail in the last lecture. After the last lecture I would like to feel that attendees had acquired not only an awareness, but a working knowledge of various aggregation techniques, and perhaps even new aggregation skills.

References

Anderson, Chris. (2004). The Long Tail. Wired Magazine, Issue 12.10 (October 2004). Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/12.10/tail.html.

Dieu, Barbara, and Vance Stevens. (2007), Pedagogical affordances of syndication, aggregation, and mash-up of content on the Web. TESL-EJ, Volume 11, Number 1: http://tesl-ej.org/ej41/int.html

Freedman, Terry (Ed.). (2004-2007). Web 2.0: About "Coming of Age: An introduction to the NEW worldwide web". http://www.terry-freedman.org.uk/db/web2/

Fryer, Wesley. (2006). Podcast103: Digital Storytelling in the Classroom. Moving at the Speed of Creativity: Wesley Fryer's conception of literacies required for the new future http://www.speedofcreativity.org/?p=1515

Grossman, Lev. (2006). Time's Person of the Year: You. Time Magazine, Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2006. http://tinyurl.com/3chjkb

Katz, Jon. (2000). Geeks: How Two Boys Rode the Internet out of Idaho. New York, Villard; described in Kennedy, William. 2003. Teaching at Tech: Educating the "Twitch Generation". Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.admin.mtu.edu/ctlfd/twitch.htm.

Laningham (2006). developerWorks Interviews: Tim Berners-Lee. IBM: http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/podcast/dwi/cm-int082206txt.html

Lessig, Lawrence. (2006). The Read-Write Society, a keynote given 15 September 2006 at the Wizards of OS4 conference. I am unable to reach the keynote URL itself at the moment, but in Lessig's abstract: "The 20th century was the only read-only century in human history, totalitarian, centralizing, controlling. The 21st is the return to read-write." http://www.wizards-of-os.org/index.php?id=2322 or http://www.wizards-of-os.org/programm/panels/authorship_amp_culture/keynote_the_read_write_society.html.

Larry Lessig has been making lectures recently where he has couched developments in Web 2.0 interactivity in the context of a trend of pendulum swings starting with the founders of the USA republic being countered by Jefferson liberalism and this finding renaissance with Lincoln but being lost again to 20th century media control until only now is the 'read-write society' re-emerging. One such talk is entitled "The Ethics of the Free Culture Movement" and was given in August, 2006 at the Wikimania Conference. The podcast of that talk is available at the archives http://wikimania2006.wikimedia.org/wiki/Archives, and is transcripted at http://lessig-transcript.blogspot.com/ (by Christopher Bradley). According to Bradley, Lessig places the democratic openness of recent improvements to 2-way interactivity of Internet sites and tools against the relatively controlling aspects of what he calls 'broadcast politics' in the 20th century, which killed of more postitive trends toward dialog and liberalism set in motion by Jefferson and Lincoln, which the totalitarian forces of the 20th century reversed. He sets the current climate of openness as a return to Jeffersonian ideals. According to Bradley, Lessig said that a book by Benkler, Wealth of Networks, http://www.benkler.org/wealth_of_networks/index.php/Main_Page was "possibly most important book of 21st century"

That is happening this century, leading to the impression that, whereas Lessig DID say that last century was the read-only century, he said that the 21st was the read-write century. He didn't actually say that exactly, I have discovered on digging about more that he has said that we are in a 'read-write society' this century, and contrasted this with the just-past 20th century, which he calls the read only one.

Locke, Christopher, Rick Levine, Doc Searls, and David Weinberger. (2001). The Cluetrain Manifesto. Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Publishing.http://www.cluetrain.com/book/index.html.

Lorenzo, Oblinger, and Dziuban. (2004). Technology and the way information is created, used, and disseminated have changed, as has the definition of "net savvy" - The original white paper from Oct 2004 is here: http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELI3008.pdfhttp://www.learningcircuits.org/2007/0207gronstedt.htm

New London Group. (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review 66 (1). Retrieved October 4, 2006 from http://wwwstatic.kern.org/filer/blogWrite44ManilaWebsite/paul/articles/A_Pedagogy_of_Multiliteracies_Designing_Social_Futures.htm or http://l-by-d.com/Multiliteracies%20HER%20Vol%2066%201996.pdf

O'Reilly, Tim. (2005). What Is Web 2.0 Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html. Hear an interview with Tim O'Reilly here: http://www.stevehargadon.com/2007/05/tim-oreilly-on-web-20-and-education.html

Prensky, Marc. (1998). Twitch Speed: Reaching Younger Workers Who Think Differently [Cover story of the January 1998 issue of The Conference Board’s magazine, Across the Board.] Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.twitchspeed.com/site/article.html.

Prensky, Marc. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. From On the Horizon (NCB University Press, Vol. 9 No. 5, October 2001). Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf#search=%22prensky%22digital%20native%22%22.

Selber, Stuart. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Sessums, Christopher. (2007). Weblog :: The Future Begins Now: School 2.0 Manifesto - Jan 31, 2007 http://elgg.net/csessums/weblog/150678.html

Stevens, Vance. (2006). Revisiting multiliteracies in collaborative learning environments: Impact on teacher professional development. TESL-EJ, Volume 10, Number 2: http://www.tesl-ej.org/ej38/int.html

Stevens, Vance. (2005). Multiliteracies for Collaborative Learning Environments. TESL-EJ Vol. 9. No. 2 (September 2005) On the Internet. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://tesl-ej.org/ej34/int.html.

Unsworth, Len. 2001. Teaching Multiliteracies across the curriculum. Buckingham - Philadelphia: Open University Press. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://mcgraw-hill.co.uk/openup/chapters/0335206042.pdf

Additional Notes

Ahtikari, Johanna and Sanna Eronen. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy - The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://kielikompassi.jyu.fi/resurssikartta/netro/gradu/index.shtml.

Chul, Lee. (2003). Peercracy: Self-Regulating Peer-to-Peer Network Using Feedback. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://ccgrid2003.apgrid.org/online_posters/posters/021.pdf.

Cross, Jay. (2003). Informal Learning – the other 80%. Internet Time Group, DRAFT, Thursday, May 08, 2003. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.internettime.com/Learning/The%20Other%2080%25.htm#_Toc40161521.

Downes, Stephen. (2005). E-learning 2.0. eLearn Magazine. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.elearnmag.org/subpage.cfm?section=articles&article=29-1.

Duber, Jim. (2002). Mad Blogs and Englishmen. TESL-EJ 6, 2 (On the Internet). Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://writing.berkeley.edu/TESL-EJ/ej22/int.html

Lebow, Jeff. (2006). Worldbridges: The Potential of Live, Interactive Webcasting. TESL-EJ, Volume 10, Number 1. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.tesl-ej.org/ej37/int.html.

Leu, Donald, Charles Kinzer, Julie Coiro, and Dana Cammack. (2004). Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other information and communication technologies. In Ruddell, Robert and Norman Unraued (Eds.). Teoretical models and processes of reading (5th edition). International Reading Association <http://www.reading.org/publications/bbv/books/bk502/toc.html>. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://www.reading.org/Library/Retrieve.cfm?D=10.1598/0872075028.54&F=bk502-54-Leu.pdf

Murray, Denise. (2000). Changing technology, changing literacy communities? Language Learning & Technology Vol. 4, No. 2, September 2000, pp. 43-58. Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://llt.msu.edu/vol4num2/murray/default.html

Prensky, Marc. (2005). "Engage Me or Enrage Me" What today's learners demand. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0553.pdf.

Siemens, George. (2005). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age George . International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 2, (1). Retrieved September 26, 2005 from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Siemens, George. (2005). Connectivism: Learning as Network-Creation. Retrieved October 4, 2006 from: http://www.learningcircuits.org/2005/nov2005/seimens.htm.

Stevens, Vance. (2004). The Skill of Communication: Technology brought to bear on the art of language learning. TESL-EJ 7, 4 (On the Internet). Retrieved October 4, 2006 from http://cwp60.berkeley.edu:16080/TESL-EJ/ej28/int.html.

Stewart, Bonnie. (2000). Techknowldege: Literate Practice and Digital Worlds http://www.egs.edu/mediaphi/pdfs/bonnie-stewart-techknowledge.pdf

Tuman, Myron. (1992). Word perfect: Literacy in the computer age. University of Pittsburg Press.

La playa on a rare sunny day (it was empty most days we were

there)

Navigate to: Writing Portal | Lecture 1 | Lecture 2 | Lecture 3

![]()

Use the navigation at

the top of this page or your browser's BACK

button to return to a previous page

For comments, suggestions, or further information on this page, contact Vance Stevens, page webmaster.

Copyright 2007 by Vance Stevens

under

Creative Commons License:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/